New Research: Cultural Explorations by Our Faculty

Our faculty members’ research has taken them all over the world, and their projects highlight the interconnected nature of language, literature, and cultural studies. These range from fiction authored during the Iran-Iraq war era, to women in science in early modern Italy, and to the contemporary detective novel in Argentina.

Dr. Ikram Masmoudi- War and occupation in Iraqi Fiction

A few years after the end of the military occupation in Iraq, the Iraqi landscape is a place where death, bloodshed, madness, and loss seem to proliferate. More than ever before, Iraq continues to monopolize the world’s attention with raging sectarian violence and the rise of non-state groups such as the Islamic State (IS). My interest in the literary reflection of what is happening in Iraq started with the 2003 invasion and the military occupation of that country. These events incited many Iraqi fiction authors to chronicle the ills of their country during the last three

decades of raw power, murderous internal wars, sanctions, and, more recently, a war of occupation. Reading this fiction coming from Iraq, I was particularly drawn to the overarching theme of the devaluation of human life, whether in the representation of the era of Saddam’s regime or in the promised democracy of the US’s involvement in Iraq.

The representation of Iraq in fiction depicts the gruesome and omnipresent reality of thanatopolitics (the mobilization of entire populations “for the purpose of wholesale slaughter in the name of life necessity”), war, and lawlessness. My investigation has been to examine how fictional Iraqi war subjects—such as the soldier, the war deserter, the suicide bomber, and the camp detainee—have coped with and withstood the subjugation of their lives to death and bloodshed during the last thirty years.

In my investigation, I have been particularly struck by the experience of the deserter in novels about the Iran-Iraq War. One of the characters I studied was “Issa,” a young marginal poet and artist portrayed in Ali Badr’s novel Asātithat al-wahm (The Professors of Illusion) who was ultimately killed for his desertion. In this work, desertion is presented as a strategy for survival under the totalitarian regime, a strategy revived and reenacted in the context of the occupation and the sectarian war.

Three decades after the Iran-Iraq war and more than a decade after the fall of Saddam’s regime, it is perplexing to see the persistence of the pattern of the deserter in the post-occupation novel, with Iraqis still fleeing their only option: death. For example, in Baghdad Marlboro by Najm Wali, the deserter becomes a trope in Iraqi culture by reflecting and symbolizing the unprotected condition of an entire people. The unnamed narrator must choose between killing an American, or being killed himself by members of Iraq’s militia. Persecuted and threatened by militia in occupied Iraq, the narrator of this novel compares his situation as an outlaw fleeing the militia to that of the war deserter. The revelation of this full circle between the Iran-Iraq war and the post-occupation novel suggests that the awful face of the past is still living with the Iraqi people, connecting a dehumanized past to a present no-less dehumanizing.

While a few of the texts I examine can be found in translation, most are unknown to the English-speaking world. By examining a wide range of authors and texts revolving around the theme of war and occupation, War and occupation in Iraqi Fiction introduces the English-speaking reader to Iraqi soul-searching in contemporary fiction.

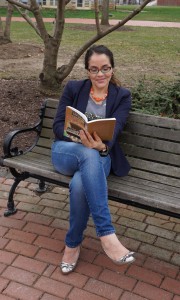

Dr. Ikram Masmoudi

Dr. Masmoudi’s book War and Occupation in Iraqi Fiction was published by Edinburgh University Press in 2015.

Dr. Meredith K. Ray – Daughters of Alchemy: Women and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy

In the story of early modern science, canonical figures loom large, threatening to eclipse the participation of lesser-known actors in this dynamic intellectual and historical moment. In my new book, Daughters of Alchemy: Women and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy (Harvard University Press, 2015), I argue that we need to reformulate our existing paradigms of scientific culture, specifically by reintroducing the integral work of women. Less visible in historical accounts than Galileo, but no less essential to the processes of cultural and epistemological change, women contributed to the evolution of scientific knowledge in crucial ways on the cusp of the Scientific Revolution.

While Daughters of Alchemy covers a range of territory, from women’s involvement with alchemy and medicine to their studies in astronomy and meteorology, the idea for the book was first sparked by an intriguing footnote I encountered while researching Caterina Sforza (1463-1509). The countess of Imola and Forlì, and one of few women rulers in Renaissance Italy, Sforza – who treated with figures such as Lorenzo de’ Medici and Machiavelli – was famed for her political acumen and military exploits. Even today, she is remembered for her political significance (and is even featured as a character in the popular videogame Assassin’s Creed II). But the footnote I came upon, buried in a hefty tome written by her nineteenth-century biographer, suggested a different side to Sforza, one even more compelling than her political activity. Sforza – the note suggested – had a keen interest in science and medicine, and had compiled a manuscript record of her experiments in these areas. Although the note was vague with respect to the whereabouts of this manuscript, I decided to start digging.

It took a little detective work, but eventually I located Sforza’s manuscript in a private archive in Italy. With

research support from a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship, I traveled there to study it in person. The beautifully preserved manuscript – titled Experimenti – contains detailed and fascinating descriptions of Sforza’s alchemical experiments, along with her efforts to produce a wide range of medicinal and cosmetic products (such as remedies for headache, stomachache, and even plague; toothpaste, lipstick, and hair color). Richly reflective of the heterogenous nature of early modern science, Sforza’s manuscript became the inspiration for my monograph. By the early sixteenth century, empirical culture was in full flower, and women were at its vanguard. Some, like Sforza, interacted with science through direct experience, growing medicinal herbs and plants in carefully designed gardens (such as the one in this photograph, taken in Florence) and conducting experiments in workshop or court settings. Others studied and wrote about science in epic poetry, treatises, and dialogues. By the early seventeenth century, the Rome-based poet Margherita Sarrocchi – as widely renowned for her erudition in natural philosophy as in literature – was corresponding with Galileo and defending his discoveries of Jupiter’s “Medicean stars” to intellectual communities throughout Italy.

Women were, in many respects, at the forefront of the new science with which Galileo is so closely associated. As I show in Daughters of Alchemy, it is not women who are missing from the picture: it is our lens that must be adjusted to perceive them.

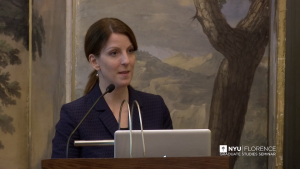

Dr. Meredith Ray

Dr. Ray’s book Daughters of Alchemy: Women and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy was published by Harvard University Press in 2015.

Dr. Cynthia Schmidt-Cruz – Buenos Aires Noir: Crime, Politics, and Society in the Argentine Novela Negra of the New Millennium

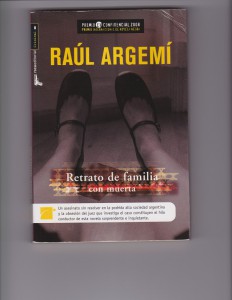

On October 27, 2002 María Marta García Belsunce met her death in her spacious home in one of the exclusive gated communities, known as “countries,” in the outskirts of Buenos Aires. María Marta’s family members and doctor said that she had suffered a domestic accident; they held a wake and interred her. But five weeks later a district attorney called for an autopsy: it revealed that five bullets had penetrated her cranium. Writer Raúl Argemí, appalled by the brazen conspiracy to cover up her murder, penned a novel inspired by the actual crime: Retrato de familia con muerta (Family Portrait with a Dead Woman). Based on the premise that the execution was linked to the family’s involvement in money laundering for a Mexican drug cartel, it is a searing criticism of a corrupt society. With its focus on the crime and its grotesque cover-up, the novel highlights the ironic contrast between the idyllic lifestyle that the “country” purportedly offers its privileged residents, and the violent and shameless behavior to which they resort to preserve their status. Retrato shares socio-political concerns with other recent Argentine novelas negras (crime novels) that critique the effects of globalization and neoliberal economic reforms.

The premise of my current book project, entitled “Buenos Aires Noir: Crime, Politics, and Society in the Argentine Novela Negra of the New Millennium,” is that the novela negra is the perfect genre to register the social malaise brought on by changes linked to market-driven economic programs. Noir sensibility captures the notion of widespread corruption and intractable socio-political problems. My study examines very recent novels—many of them heretofore unstudied— that paint a portrait of Argentine and Latin American reality through the lens of crime. Some thematic issues I address include organized crime and institutional complicity, political scandals during the presidency of Carlos Menem (1989-1999), terrorist attacks on Jewish institutions in Buenos Aires, and the “winners” and the “losers” of market-based structural changes.

My analysis highlights major tendencies in contemporary Argentine and Latin American crime fiction. Unlike the classic version of the detective genre—think Sherlock Holmes and Agatha Christie—in which the crime is always solved and justice is done, in the Latin American crime novel the wrongdoers invariably go unpunished. The absence of the detective is the norm and frequently an investigative journalist carries out the detective function. While some novels reiterate hard-boiled fiction’s typical misogynist representation of women with its requisite femme fatale, others reverse patriarchal ideology by portraying smart and savvy female journalists. The mapping of Buenos Aires is an integral part of the novels; frequent mention of streets, neighborhoods, and other points of reference in the city produce schemes of meaning such as the marking of social class and uneven modernization. Another finding is surprising and illuminating and has to do with the dual conclusions of several novels. While crime and chaos prevail on a societal level, sentimentality wins out on a personal level as the world-weary investigators are rewarded for their diligence with a fresh chance at love. Thus in the face of societal anomie, the writers envision human bonding as a type of antidote, or at least a consolation.

Dr. Cynthia Scmidt-Cruz

Dr. Schmidt-Cruz is currently working on her book project Buenos Aires Noir: Crime, Politics, and Society in the Argentine Novela Negra of the New Millennium.

This entry was posted in Polyglot and tagged Arabic, Current Issue, Fall 2015 Polyglot, Italian, Spanish.