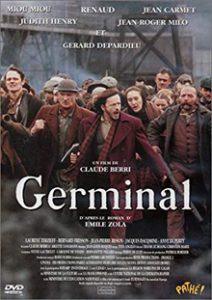

Germinal

The story is a simple one. We meet the Maheu family, who live crowded together in a cold and smoky cottage not far from the mines. They do backbreaking work to earn their living, and expect their children to do the same; indeed, the mother frankly states that one reason for having children is so that they can work, and bring more money to the family. The wages in the local pits seem carefully calculated down to the last franc, to support life and the ability to work while not providing one franc more. The miners are unable ever to gather enough capital to leave the district, or to make a different choice of work. They are trapped between servitude and starvation.

In the mines, working conditions are hazardous. The miners are responsible for shoring up the shafts with timber, but are not paid extra for this work, so every moment spent timbering comes out of their own pockets. Understandably, they prefer to dig coal. Also understandably, there are many mine accidents, each one expensive for the rich owners, who propose a scheme in which timbering will be paid for, but the price paid for coal will be reduced. The result will be even smaller wages.

Berri lays this groundwork against a backdrop of the daily life in the district, as season follows season and the workers struggle to maintain even simple humanity in the face of their grim conditions. Meanwhile, we see the lives of the mine owners and managers, with their great houses, their Paris fashions, their carriages, their banquets and parties. Berri is fond of cutting back and forth between poverty and affluence, as Zola was in his novel, and the message is unmistakable: The owners are stealing the fruits of the workers’ labor. One day, the miners decide to go on strike, and the authorities repress them.