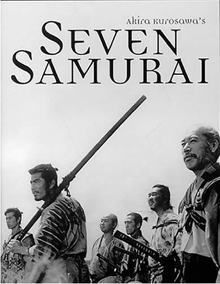

Seven Samurai

A samurai answers a village’s request for protection after he falls on hard times. The town needs protection from bandits, so the samurai gathers six others to help him teach the people how to defend themselves, and the villagers provide the soldiers with food. A giant battle occurs when forty bandits attack the village.

The purpose of Seven Samurai was to make a samurai movie that was anchored in ancient Japanese culture and yet argued for a flexible humanism in place of rigid traditions. One of the central truths of Seven Samurai is that the samurai and the villagers who hire them are of different castes and must never mix. Indeed, we learn that these villagers had earlier been hostile to samurai–and one of them, even now, hysterically fears that a samurai will make off with his daughter. Yet the bandits represent a greater threat, and so the samurai are hired, valued and resented in about equal measure.

Both sides, the bandits and samurai, are bound by the roles imposed on them by society, and in To the Distant Observer, his study of Japanese films, Noel Burch observes: “masochistic perseverance in the fulfillment of complex social obligations is a basic cultural trait of Japan.” Not only do the samurai persevere, but so do the bandits, who continue their series of raids even though it is clear the village is well-defended, that they are sustaining heavy losses, and that there must be unprotected villages somewhere close around. Like characters in a Greek tragedy, they perform the roles they have been assigned.